The scene is an art studio in Clarion, PA, sometime in 1980-1981. Al Charley was an art professor at Clarion State College, a sculptor, and a guy who always made me think of Ken Kesey because they both were artists who’d been champion wrestlers in their youth. There’s something about former wrestlers, something centered about their personalities. I don’t think I have ever met a former wrestler that I didn’t take an immediate liking to. The same is true for physicists, though I don’t really know why. Maybe it’s all the mental wrestling with the fundamental nature of the universe that gives them a similar edge. You might think the same would be true for philosophers or artists but it isn’t. It’s easier for a philosopher to just completely fake it than for a wrestler or physicist. There’s not the arm of someone who isn’t faking it wrapped around your throat; nor is there any math. And I don't know if "faking it" even makes sense in refence to art.

But I digress.

This story involves a cast of characters that include George Barber, Henry Miller, Gilbert Neiman, Man Ray, Earnest Hemmingway and Allen Ginsberg’s father. It may take a while, but it will be worth your time.

George Barber was a professor of English at Clarion State College in Western Pennsylvania, arriving there sometime in the late 1950s (maybe the early 60s) I think. It was George who gave me the answer to a question I had after my first few years at Clarion. During my first year I encountered an array of the most interesting people I’d ever met, people from the arts, sciences, from everywhere, and I was puzzled by how they all arrived in this remote little town of 6,000 hidden in the hills of rural Pennsylvania. George told me that you would find a population of east coast intellectuals stuck away in every small nondescript state college across the eastern half of the country because that’s where they all went to hide in the face of Joe McCarthy and the “red scare” of the 1950s. They taught their classes and lived quiet lives, received the slight protections that academic tenure provides and plugged away in sections of basic composition and surveys of English Lit until they could retire and go off into a forest somewhere and read.

Some would go on to write. A younger colleague of George’s, Terry Caesar, later wrote the finest book about the experience of being an academic I’ve ever found or hope to find,

Conspiring with Forms: Life in Academic Texts (University of Georgia Press, 1992). That book reprints Caesar’s earlier essay “On Teaching at a Second-Rate University,” whose publication made his life at Clarion… interesting. Hard to find now, but well worth your trouble.

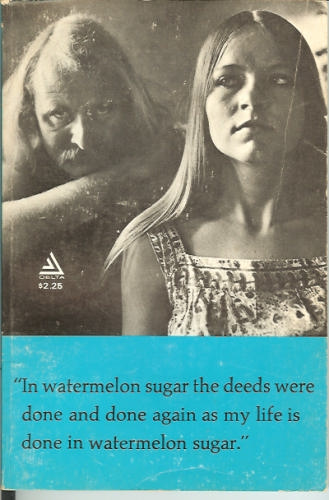

In 1947, another Clarion refugee had written

There’s a Tyrant in Every Country, of which Henry Miller said. “Myself, I’ve never read a better novel about Mexico.”

For a time, Gilbert Neiman lived near Miller in Big Sur and is written about by Miller in his book,

Big Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. The excerpt below is from the last part of the section about Gilbert:

The Music! One night, about two in the morning, the door of our shack was thrown open with a bang and, before I knew what was happening, I felt a hand gripping my throat, squeezing it viciously. I knew damn well I wasn’t dreaming. The a voice, a boozy voice which I recognized instantly and which sounded maudlin and terrifying, shouted in my ear, “Where’s that damned gadget?” “What gadget?” I gurgled, struggling to release the grip around my throat. “The radio! Where are you hiding it?” With this he let go his grip and began dismantling the place. I sprang out of bed and tried to pacify him. “You know I have no radio,” I shouted. “What’s the matter with you? What’s eating you?”

He ignored me, went on pushing things aside, tearing at the walls with furious talons, upsetting chinaware and pots and pans. Finding nothing, he soon relented, though still furious, still cursing and swearing. I thought he had gone out of his mind. “What is it, Gilbert? What’s happened?” I was holding him by the arm. “What is it?” he yelled, and I could feel his glare even through the darkness. “What is it? Come on out here!” He grabbed my arm and started dragging me. After we had gone a few yards in the direction of his house he stopped suddenly, and gripping me like a demon, he shouted: “Now! Now do you hear?” “Hear what?” I said innocently. “The music! It’s the same tune all the time. It’s driving me crazy.” “Maybe it’s coming from your place,” I said, though I knew damned well it was coming from inside him. “So you know where it is,” said Gilbert, accelerating his pace and dragging me along like a dead horse. Under his breath he mumbled something about my “cunning” ways. When we got to his house he dropped to his knees and began sniffing around, just like a dog in the bushes and under the porch. To humor him, I also got down on all fours, to search for the concealed gadget that was giving out Beethoven’s Fifth. After we had crawled around the house and under it as far as we could, we lay on our backs and looked up at the stars. “It’s stopped,” said Gilbert. “Did you notice?” “You’re crazy,” I said. “It never stops.” “Tell me honestly,” he said, in a conciliating tone of voice, “where did you hide it?” “I never hid anything,” I said. “It’s there . . . in the stream. Can’t you hear it?” “He turned over on the other side and cupped his ear, straining every nerve to hear."I don't hear a thing," he said. "That's strange," said I. "Listen! It's Smetana now. You know the one . . . Out Of My Life. It's as clear as can be, every note." He turned over on the other side and again he cupped his ear. He held this position for a few moments then rolled over on his back, smiling the smile of an angel. He gave a little laugh, then said: “I know now . . . I was dreaming. I was dreaming that I was the conductor of an orchestra. . . . “ I cut him short. “But how do you explain the other times?” “Drink,” he said. “I drink too much.” “No you don’t,” I replied, “I hear it just the same as you. Only I know where it comes from.” “Where?” said Gilbert. “I told you . . . from the stream.” “You mean someone has hidden it in the creek?” “Exactly,” I said. I allowed a due pause, then added: “Do you know who?” “No,” he said. “God!” He began to laugh like a madman. “God!” he yelled “God!” Then louder and louder. “God, God, God, God, God! Can you beat that?” He was now convulsed with laughter. I had to shake him to make him listen to me. “Gilbert,” I said, just as gently as could be, “if you don’t mind, I’m going back to bed. You go down by the creek and look for it. It’s under a mossy rock on the left hand side near the bridge. Don’t tell anybody, will you?” I stood up and shook hands with him. “Remember,” I said, “not a soul!” He put his fingers to his lips and went “Shhhh! Shhhh!” (pages 73-75)

When I got to Clarion in the Summer of 1971 Gilbert was teaching in the English department. He was a raging alcoholic and students avoided his classes as much as was possible. He would stagger into his Shakespeare class and talk for an hour about Ginsburg’s

Howl, and then spend an hour in his American Poetry class diving into the subtext of

The Tempest.

I signed up for one of his classes, I don’t remember what it was, but I was 17 and not at all prepared to be in the presence of that much pain. I dropped the class after one session.

In 1980 I was living in Clarion again. Gilbert’s alcoholism had reached such epic proportions that the college finally revoked his tenure and fired him. He died very quickly after that. Some people felt that the college dismissing him was what killed him, others felt that he would have died on schedule regardless. A story circulated that, like the story that was told after Dylan Thomas died, when an autopsy was performed and the coroner opened him up the room was immediately filled with the overpowering smell of whiskey.

Back to the Art Department and Al Charley….

One afternoon I went into the foundry and up to Al’s office. I was working in the University’s TV studios and Al wanted to record some things he was working on. What it turned out to be was simply a video record; Al would stand in a single light in front of a permanent living room set that took up one corner of the studio where a cable exercise show was taped. The program was

The Paul Gaudino Family Fitness Hour which, in 2007, is still running and is now enshrined in the Guiness Book of Records as the longest running exercise program in TV history. I ran a studio camera for the program back in the day when you could still smoke in the studio during a production so long as you had something to use as an ashtray. Al brought a notebook with him and he would read from it; mostly fragments and partial ideas. I think he was just in a very preliminary stage of thinking about how video might be used in his work.

When I went into his office I noticed some bandages on his hands. He told me he’d gone over to visit Gilbert’s widow. She let him in and they went out to the back of the house where she’d built a fire and was burning some of Gilbert’s things. His hands were bandaged because he’d burnt them reaching into the fire to pull out a shoe box. He showed me the box, it was burnt on the bottom and around the edges of the lid. Then he opened it.

I’ve never had any experience that is anything like the experience of going through the papers that were inside the scorched box. I wish my memory were better. I wish I’d just made an inventory. Gilbert had been good friends with the artist Man Ray and there was a stack of cards that Man Ray had sent Gilbert over the years to mark special occasions, Christmas, birthdays, etc. These cards were a thick cardboard onto which was stitched with thread an original black & white photograph. The backs were covered with notes in Man Ray’s hand. The photos were all unique and I do not believe they have ever been published anywhere.

Then there were the letters. There were letters from Hemmingway. Letters from Allen Ginsberg’s father filled with worry over his strange son. Letters from various people I was not well read enough to recognize. And one large stack of letters from Henry Miller tied together with a piece of twine.

I sat there and read letter after letter. In one, Miller was describing some pornography he’d seen recently; it was hilarious and explicit. There was one that sticks out from all the others. In it, Miller was replying to a letter Gilbert had sent in which he was worried about being drafted. Gilbert was asking Henry's advice, he was thinking about posing as a homosexual or dope addict to get out of the military if he was called up.

Miller’s letter was handwritten and his advice to Gilbert was to not do any of those things. Instead, and he wrote this in

enormous letters at an angle taking up the better part of the page,

"Be a DOPE!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! Nobody wants a dope!!!”

He went on to describe how Gilbert should be the most positive, helpful, energetic, friendly, eager completely bumbling incompetent moron possible!

As I read it I realized that Henry Miller had just sketched out the pilot episode of

Gomer Pyle U.S.M.C.The letters the photos, were a pirate’s treasure chest, burnt around the edges. After an hour or so I came up for air.

“Jesus… Al…. I….”

“I know.” He said.

“I’d like to look through all these Miller letters, could I take them for a little while?” I could barely believe the words as they came out of my mouth, but my mother had advised “You’ll never know if you don’t ask,” advice that, in hindsight I now realize, if I’d have taken more to heart in the 70s I’m sure I would have gotten more sex. A lot more.

But I digress.

Al told me I could take them for a day but that I had to promise that I wouldn’t photocopy them. I thought about it for a moment and, in a rare and completely inappropriate moment of honesty said, “Al, you’re my friend, so I have to tell you that if I take these I’ll go to a Xerox machine so fast I may travel back in time.”

That was the first thing I regret doing in reference to the shoebox.

My second regret was that I didn’t follow my instinct the afternoon I dropped by the college graphics department to say hello to my two friends, Nancy and Mary, who worked there. It was around lunch time and the place was empty, the building was deserted. On the table in the middle of the room were about a dozen of the Man Ray photo postcards, waiting to be photographed. For a moment I thought about taking 3 or 4 of these, but changed my mind and left. Damn.

A little while after that Al Charley got some sort of grant to fund a larger project on Man Ray that would produce a book. The money would have allowed him to spend time in Paris and work with some other Man Ray collections.

A little while after that Al was driving home from Clarion one evening and was killed in a collision with a coal truck.

I don’t remember the dates but I think he died around 1983-1984, shortly after I left Clarion again and moved to Ohio.

I never found out what happened next. I don’t know what happened to that shoebox; I have had a dream in which Al’s widow is placing it into a fire in her back yard. I doubt that would happen. But, to this day, I wonder about those letters from Henry Miller. I wonder if Al, Gilbert, Henry and I remain the only people who have ever read them. Over the years I have mentioned the shoebox to writers and artists and scholars I’ve met, here and in France, but I don’t think I’ve ever managed to get anyone interested in trying to track them down. I imagine starting in Clarion’s art department and asking about Al’s widow would be a start.

A year or so ago I was in a writer's group and I came up with an exercise that involved writing on slips of paper the first lines of every song on The Beatles' White Album and handing them out. The idea is that the paper is no longer blank once you copy that line, where you go can be anywhere, though you should have no connection with whatever narrative might be in the song.

A year or so ago I was in a writer's group and I came up with an exercise that involved writing on slips of paper the first lines of every song on The Beatles' White Album and handing them out. The idea is that the paper is no longer blank once you copy that line, where you go can be anywhere, though you should have no connection with whatever narrative might be in the song.