Sunday, January 30, 2011

Honey, can I jump on it sometime?

Well, I see you got your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Yes, I see you got your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Well, you must tell me, baby

How your head feels under somethin’ like that

Under your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Well, you look so pretty in it

Honey, can I jump on it sometime?

Yes, I just wanna see

If it’s really that expensive kind

You know it balances on your head

Just like a mattress balances

On a bottle of wine

Your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Well, if you wanna see the sun rise

Honey, I know where

We’ll go out and see it sometime

We’ll both just sit there and stare

Me with my belt

Wrapped around my head

And you just sittin’ there

In your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Well, I asked the doctor if I could see you

It’s bad for your health, he said

Yes, I disobeyed his orders

I came to see you

But I found him there instead

You know, I don’t mind him cheatin’ on me

But I sure wish he’d take that off his head

Your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Well, I see you got a new boyfriend

You know, I never seen him before

Well, I saw him

Makin’ love to you

You forgot to close the garage door

You might think he loves you for your money

But I know what he really loves you for

It’s your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat

Copyright © 1966 by Dwarf Music; renewed 1994 by Dwarf Music

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Bob Dylan: Asking Questions About "Mississippi"

Every step of the way we walk the line

Every step of the way we walk the lineYour days are numbered, so are mine

Time is pilin' up, we struggle and we scrape

We're all boxed in, nowhere to escape

City's just a jungle, more games to play

Trapped in the heart of it, trying to get away

I was raised in the country, I been workin' in the town

I been in trouble ever since I set my suitcase down

Got nothing for you, I had nothing before

Don't even have anything for myself anymore

Sky full of fire, pain pourin' down

Nothing you can sell me, I'll see you around

All my powers of expression and thoughts so sublime

Could never do you justice in reason or rhyme

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

Well, the devil's in the alley, mule's in the stall

Say anything you wanna, I have heard it all

I was thinkin' about the things that Rosie said

I was dreaming I was sleeping in Rosie's bed

Walking through the leaves, falling from the trees

Feeling like a stranger nobody sees

So many things that we never will undo

I know you're sorry, I'm sorry too

Some people will offer you their hand and some won't

Last night I knew you, tonight I don't

I need somethin' strong to distract my mind

I'm gonna look at you 'til my eyes go blind

Well I got here following the southern star

I crossed that river just to be where you are

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

Well my ship's been split to splinters and it's sinking fast

I'm drownin' in the poison, got no future, got no past

But my heart is not weary, it's light and it's free

I've got nothin' but affection for all those who've sailed with me

Everybody movin' if they ain't already there

Everybody got to move somewhere

Stick with me baby, stick with me anyhow

Things should start to get interesting right about now

My clothes are wet, tight on my skin

Not as tight as the corner that I painted myself in

I know that fortune is waitin' to be kind

So give me your hand and say you'll be mine

Well, the emptiness is endless, cold as the clay

You can always come back, but you can't come back all the way

Only one thing I did wrong

Stayed in Mississippi a day too long

"Mississippi" is one amazing Dylan song for a variety of reasons. Of all the songs that get placed on a "Dylan's best song" list, "Mississippi" seems, to me, the most ephemeral of all. While songs like "Visions of Johanna" "Desolation Row" "Chimes of Freedom" clearly aren't traditional "story telling" songs, they none the less are chock full of images; they are overflowing with meaning, whereas "Mississippi" seems to barely trickle meaning, is more like a leaky faucet than the burst dams of those other songs.

More than any other Dylan song it seems like some odd alchemy of words that barely whisper meaning mixed with a strong performance create a result that is so surprisingly impressive. All the various versions (see here, here and here) lead up to the final album version and that version is clearly the best because it finds that amazing contrast between a lyric that descends into a sort of darkness sung against a progression that ascends into light, counteracting the despair.

One way the song works in to create a sense of urgency in the opening verse. "Our days are numbered, there's no escape." A good chunk of Dylan's best work sets up a dichotomy of "light/dark" "urban/rural" and this does too in the second verse's "I was raised in the country, I been workin' in the town."

The song's structure is comprised of 12 verses arranged in three sets of four verses each and each of those three sets leading up to the repeating enigma: "Only one thing I did wrong / Stayed in Mississippi a day too long."

Here's where the greater context of Love and Theft enters the picture and contributes meaning to "Mississippi." Mississippi has nothing to do with the song per se, but fits into the larger puzzle of the record as a kind of tour through the reconstructed South.

Sung in the first person, it has a narrator; it's just that the narrator is less forthcoming than any other on any other song. To fill 12 verses and say.... almost nothing. It’s like a Steely Dan song.

"Mississippi" is a perfect example of a Dylan song that really resists "interrogation" (you could water board this song and it still isn't giving anything up). But there are two different approaches -- in the first you take a song, sit it in a chair and shine a 100 watt light in its eyes and ask it where it was on the evening of October 5th. That won't work here.

It is the other approach that works -- you take the song to the pub, not to "get it drunk" but to get drunk with it. You sit and drink 6 pints each and it tells you its secrets as you tell it a few of your own.

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

Bob Dylan: "Floater (Too Much To Ask)"

Recently, I spent the first half of a day listening to the last three albums by Bob Dylan in the order of their release: Love and Theft (2001), Modern Times (2006) and Together Through Life (2009). Each record shares the trait of all great art in rewarding repeat visits. It wasn’t until sometime in 2003 that I realized that Love and Theft was the best album Dylan had ever made. Right now I am of the opinion that Modern Times has the slightest edge over the other two.

The writing on all three is some of Dylan’s best, but the writing on Love and Theft is particularly rich. At the half-way point, the song “Floater (Too Much To Ask)” shows up. Musically, the album is a tour of the popular music of America in the 20th Century, and this song sounds like something from the 1930s-1940s. Lyrically, however, its sixteen verses seem to flash on the screen like scratchy black & white home movies from rural Tennessee circa 1938.

Down over the window

Comes the dazzling sunlit rays

Through the back alleys - through the blinds

Another one of them endless days

Honeybees are buzzin'

Leaves begin to stir

I'm in love with my second cousin

I tell myself I could be happy forever with her

I keep listenin' for footsteps

But I ain't hearing any

From the boat I fish for bullheads

I catch a lot, sometimes too many

A summer breeze is blowing

A squall is settin' in

Sometimes it's just plain stupid

To get into any kind of wind

The character who sings the song is a gentleman we only ever see out of the corner of our eye as we look at the various things he’s describing. Sometimes he describes aspects of everyday life, but other times he describes his own inner thoughts and feelings and we are offered little insights into his psyche.

The old men 'round here, sometimes they get

On bad terms with the younger men

But old, young, age don't carry weight

It doesn't matter in the end

One of the boss' hangers-on

Comes to call at times you least expect

Try to bully ya - strong arm you - inspire you with fear

It has the opposite effect

As the song proceeds it builds up this rhythm moving back and forth between description and autobiography.

There's a new grove of trees on the outskirts of town

The old one is long gone

Timber two-foot six across

Burns with the bark still on

They say times are hard, if you don't believe it

You can just follow your nose

It don't bother me - times are hard everywhere

We'll just have to see how it goes

My old man, he's like some feudal lord

Got more lives than a cat

Never seen him quarrel with my mother even once

Things come alive or they fall flat

Even in the technology stock boom of the 1990s you’d still have been safe singing about times being hard. Times are always hard (and, for that matter, always changing).

You can smell the pine wood burnin'

You can hear the school bell ring

Gotta get up near the teacher if you can

If you wanna learn anything

Romeo, he said to Juliet, "You got a poor complexion.

It doesn't give your appearance a very youthful touch!"

Juliet said back to Romeo, "Why don't you just shove off

If it bothers you so much."

They all got out of here any way they could

The cold rain can give you the shivers

They went down the Ohio, the Cumberland, the Tennessee

All the rest of them rebel rivers

I wonder if, as he’s spun this tale, this man has been sipping something a bit stronger than sweet tea. We’re offered advice (“Sit close to the teacher”), some thoroughly odd and oblique Shakespeare reference, and that utterly fantastic alliteration, “rest of them rebel rivers.”

I wonder about how alcohol effects people differently when he suddenly stops to remind us:

If you ever try to interfere with me or cross my path again

You do so at the peril of your own life

I'm not quite as cool or forgiving as I sound

I've seen enough heartaches and strife

The moment passes, and we move back to autobiography.

My grandfather was a duck trapper

He could do it with just dragnets and ropes

My grandmother could sew new dresses out of old cloth

I don't know if they had any dreams or hopes

I had 'em once though, I suppose, to go along

With all the ring dancin' Christmas carols on all of the Christmas Eves

I left all my dreams and hopes

Buried under tobacco leaves

Perhaps that’s it then; our slightly tipsy narrator has lived his life as a tobacco farmer, running a plantation, his own “dreams and hopes left buried under tobacco leaves.”

And as I think about it, I can’t stop myself from wondering if, thirty-seven years after he condemned him in his most famous self-righteous and criminally distorted “finger pointing” protest songs, Bob Dylan is writing this song from the point of view of an older William Devereux "Billy" Zantzinger.

No matter. The first fifteen verses were just passing the time up to where, his eyes downcast, we’re told that:

It's not always easy kicking someone out

Gotta wait a while - it can be an unpleasant task

Sometimes somebody wants you to give something up

And tears or not, it's too much to ask.

Tuesday, July 14, 2009

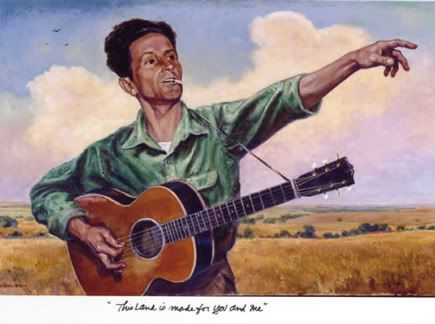

Last Thoughts On Woody Guthrie....

"Okemah was one of the singiest, square dancingest, drinkingest, yellingest, preachingest, walkingest, talkingest, laughingest, cryingest, shootingest, fist fightingest, bleedingest, gamblingest, gun, club and razor carryingest of our ranch towns and farm towns, because it blossomed out into one of our first Oil Boom Towns." - Woody Guthrie

"Okemah was one of the singiest, square dancingest, drinkingest, yellingest, preachingest, walkingest, talkingest, laughingest, cryingest, shootingest, fist fightingest, bleedingest, gamblingest, gun, club and razor carryingest of our ranch towns and farm towns, because it blossomed out into one of our first Oil Boom Towns." - Woody GuthrieToday is Woody's 97th birthday and time to take a moment and remember that we are standing today on the very first rung of a ladder that leads to the America that Woody imagined it might be possible to have. Say it with me, say it out loud and look at the words as they hang suspended in the air; say it every morning like a mantra.... This land in our land.

Woodrow Wilson Guthrie was born on July 14, 1912, in Okemah, Oklahoma. He was the second-born son of Charles and Nora Belle Guthrie. His father – a cowboy, land speculator, and local politician – taught Woody Western songs, Indian songs, and Scottish folk tunes. His Kansas-born mother, also musically inclined, had an equally profound effect on Woody.

Of all the artists that Woody Guthrie influenced, none is more important than Bob Dylan. Like Ramblin' Jack Elliot before him, a young Robert Zimmerman read Guthrie's Bound For Glory and set out on the road, reinventing himself with every step he took. His steps led him to Brooklyn State Hospital where Guthrie was dying from Huntington's Disease. By the time of Dylan's first album in 1962 he'd written "Song To Woody" which described the debt he owed.

I'm out here a thousand miles from my home,

Walkin' a road other men have gone down.

I'm seein' your world of people and things,

Your paupers and peasants and princes and kings.

Hey, hey Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

'Bout a funny ol' world that's a-comin' along.

Seems sick an' it's hungry, it's tired an' it's torn,

It looks like it's a-dyin' an' it's hardly been born.

Hey, Woody Guthrie, but I know that you know

All the things that I'm a-sayin' an' a-many times more.

I'm a-singin' you the song, but I can't sing enough,

'Cause there's not many men that done the things that you've done.

Here's to Cisco an' Sonny an' Leadbelly too,

An' to all the good people that traveled with you.

Here's to the hearts and the hands of the men

That come with the dust and are gone with the wind.

I'm a-leaving' tomorrow, but I could leave today,

Somewhere down the road someday.

The very last thing that I'd want to do

Is to say I've been hittin' some hard travelin' too.

On a regular basis I seem to get into arguments with Bob Dylan fans about whether Dylan is a "poet" or not. What I hear in their arguments is an attempt to, in effect, promote Dylan from mere "songwriter" to "poet" and award him status that reflects the age-old "high culture" versus "low culture" (or elite vs pop) dichotomy, the very dichotomy that artists like Dylan upended and overturned a good forty years ago or more.

Their arguments are what arguing that Arthur Miller was such a good playwright that we ought to call him a "novelist" would be like, if anyone ever argued such a thing.

But Dylan has, on occasion, written poetry; and I believe that any serious anthology of the best 20th Century American poetry would do well to include his poem "Last Thoughts On Woody Guthrie." The video has the audio recording of Dylan's reading of the poem at a Town Hall concert in April of 1963 (recorded for a planned live LP that was never released). It is Bob, not as Rimbaud or Verlaine, but as Whitman.

Last Thoughts On Woody Guthrie

When yer head gets twisted and yer mind grows numb

When you think you're too old, too young, too smart or too dumb

When yer laggin' behind an' losin' yer pace

In a slow-motion crawl of life's busy race

No matter what yer doing if you start givin' up

If the wine don't come to the top of yer cup

If the wind's got you sideways with with one hand holdin' on

And the other starts slipping and the feeling is gone

And yer train engine fire needs a new spark to catch it

And the wood's easy findin' but yer lazy to fetch it

And yer sidewalk starts curlin' and the street gets too long

And you start walkin' backwards though you know its wrong

And lonesome comes up as down goes the day

And tomorrow's mornin' seems so far away

And you feel the reins from yer pony are slippin'

And yer rope is a-slidin' 'cause yer hands are a-drippin'

And yer sun-decked desert and evergreen valleys

Turn to broken down slums and trash-can alleys

And yer sky cries water and yer drain pipe's a-pourin'

And the lightnin's a-flashing and the thunder's a-crashin'

And the windows are rattlin' and breakin' and the roof tops a-shakin'

And yer whole world's a-slammin' and bangin'

And yer minutes of sun turn to hours of storm

And to yourself you sometimes say

"I never knew it was gonna be this way

Why didn't they tell me the day I was born"

And you start gettin' chills and yer jumping from sweat

And you're lookin' for somethin' you ain't quite found yet

And yer knee-deep in the dark water with yer hands in the air

And the whole world's a-watchin' with a window peek stare

And yer good gal leaves and she's long gone a-flying

And yer heart feels sick like fish when they're fryin'

And yer jackhammer falls from yer hand to yer feet

And you need it badly but it lays on the street

And yer bell's bangin' loudly but you can't hear its beat

And you think yer ears might a been hurt

Or yer eyes've turned filthy from the sight-blindin' dirt

And you figured you failed in yesterdays rush

When you were faked out an' fooled white facing a four flush

And all the time you were holdin' three queens

And it's makin you mad, it's makin' you mean

Like in the middle of Life magazine

Bouncin' around a pinball machine

And there's something on yer mind you wanna be saying

That somebody someplace oughta be hearin'

But it's trapped on yer tongue and sealed in yer head

And it bothers you badly when your layin' in bed

And no matter how you try you just can't say it

And yer scared to yer soul you just might forget it

And yer eyes get swimmy from the tears in yer head

And yer pillows of feathers turn to blankets of lead

And the lion's mouth opens and yer staring at his teeth

And his jaws start closin with you underneath

And yer flat on your belly with yer hands tied behind

And you wish you'd never taken that last detour sign

And you say to yourself just what am I doin'

On this road I'm walkin', on this trail I'm turnin'

On this curve I'm hanging

On this pathway I'm strolling, in the space I'm taking

In this air I'm inhaling

Am I mixed up too much, am I mixed up too hard

Why am I walking, where am I running

What am I saying, what am I knowing

On this guitar I'm playing, on this banjo I'm frailin'

On this mandolin I'm strummin', in the song I'm singin'

In the tune I'm hummin', in the words I'm writin'

In the words that I'm thinkin'

In this ocean of hours I'm all the time drinkin'

Who am I helping, what am I breaking

What am I giving, what am I taking

But you try with your whole soul best

Never to think these thoughts and never to let

Them kind of thoughts gain ground

Or make yer heart pound

But then again you know why they're around

Just waiting for a chance to slip and drop down

"Cause sometimes you hear'em when the night times comes creeping

And you fear that they might catch you a-sleeping

And you jump from yer bed, from yer last chapter of dreamin'

And you can't remember for the best of yer thinking

If that was you in the dream that was screaming

And you know that it's something special you're needin'

And you know that there's no drug that'll do for the healin'

And no liquor in the land to stop yer brain from bleeding

And you need something special

Yeah, you need something special all right

You need a fast flyin' train on a tornado track

To shoot you someplace and shoot you back

You need a cyclone wind on a stream engine howler

That's been banging and booming and blowing forever

That knows yer troubles a hundred times over

You need a Greyhound bus that don't bar no race

That won't laugh at yer looks

Your voice or your face

And by any number of bets in the book

Will be rollin' long after the bubblegum craze

You need something to open up a new door

To show you something you seen before

But overlooked a hundred times or more

You need something to open your eyes

You need something to make it known

That it's you and no one else that owns

That spot that yer standing, that space that you're sitting

That the world ain't got you beat

That it ain't got you licked

It can't get you crazy no matter how many

Times you might get kicked

You need something special all right

You need something special to give you hope

But hope's just a word

That maybe you said or maybe you heard

On some windy corner 'round a wide-angled curve

But that's what you need man, and you need it bad

And yer trouble is you know it too good

"Cause you look an' you start getting the chills

"Cause you can't find it on a dollar bill

And it ain't on Macy's window sill

And it ain't on no rich kid's road map

And it ain't in no fat kid's fraternity house

And it ain't made in no Hollywood wheat germ

And it ain't on that dimlit stage

With that half-wit comedian on it

Ranting and raving and taking yer money

And you thinks it's funny

No you can't find it in no night club or no yacht club

And it ain't in the seats of a supper club

And sure as hell you're bound to tell

That no matter how hard you rub

You just ain't a-gonna find it on yer ticket stub

No, and it ain't in the rumors people're tellin' you

And it ain't in the pimple-lotion people are sellin' you

And it ain't in no cardboard-box house

Or down any movie star's blouse

And you can't find it on the golf course

And Uncle Remus can't tell you and neither can Santa Claus

And it ain't in the cream puff hair-do or cotton candy clothes

And it ain't in the dime store dummies or bubblegum goons

And it ain't in the marshmallow noises of the chocolate cake voices

That come knockin' and tappin' in Christmas wrappin'

Sayin' ain't I pretty and ain't I cute and look at my skin

Look at my skin shine, look at my skin glow

Look at my skin laugh, look at my skin cry

When you can't even sense if they got any insides

These people so pretty in their ribbons and bows

No you'll not now or no other day

Find it on the doorsteps made out-a paper mache¥

And inside it the people made of molasses

That every other day buy a new pair of sunglasses

And it ain't in the fifty-star generals and flipped-out phonies

Who'd turn yuh in for a tenth of a penny

Who breathe and burp and bend and crack

And before you can count from one to ten

Do it all over again but this time behind yer back

My friend

The ones that wheel and deal and whirl and twirl

And play games with each other in their sand-box world

And you can't find it either in the no-talent fools

That run around gallant

And make all rules for the ones that got talent

And it ain't in the ones that ain't got any talent but think they do

And think they're foolin' you

The ones who jump on the wagon

Just for a while 'cause they know it's in style

To get their kicks, get out of it quick

And make all kinds of money and chicks

And you yell to yourself and you throw down yer hat

Sayin', "Christ do I gotta be like that

Ain't there no one here that knows where I'm at

Ain't there no one here that knows how I feel

Good God Almighty

THAT STUFF AIN'T REAL"

No but that ain't yer game, it ain't even yer race

You can't hear yer name, you can't see yer face

You gotta look some other place

And where do you look for this hope that yer seekin'

Where do you look for this lamp that's a-burnin'

Where do you look for this oil well gushin'

Where do you look for this candle that's glowin'

Where do you look for this hope that you know is there

And out there somewhere

And your feet can only walk down two kinds of roads

Your eyes can only look through two kinds of windows

Your nose can only smell two kinds of hallways

You can touch and twist

And turn two kinds of doorknobs

You can either go to the church of your choice

Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital

You'll find God in the church of your choice

You'll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital

And though it's only my opinion

I may be right or wrong

You'll find them both

In the Grand Canyon

At sundown

- Bob Dylan

As an added bonus for those of you unfamiliar with a series of songs Guthrie was commissioned by the US Department of Health to write about the dangers of venereal disease (which, upon hearing, were pretty much never heard from again) you can go here and find the lyrics and mp3s of Bob Dylan playing all four songs: "VD Blues", "VD Gunner's Blues" (aka "Landlady"), "VD Seaman's Last Letter", and "VD Waltz." Here's a brief sample:

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Why I love Carrie Fisher....

Nathan Rabin writes:

Carrie Fisher’s life is a perfect storm of funny. Not many folks are privileged enough to have Bob Dylan show up at one of their cocktail parties wearing a parka and sunglasses. Even fewer are capable of coming up with the perfect zinger for the occasion:

“Thank God you wore that, Bob, because sometimes late at night here the sun gets really, really bright, then it snows.”

From Fisher's wonderful new book, Wishful Drinking.

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Translations of the Hanging....

Lastly, T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land also appears to have influenced "Desolation Row." T. S. Eliot had died earlier in 1965.

И красят стены в чёрный цвет.

Сегодня в цирке представленье,

Но на него билетов нет.

Everything in the world is for sale,

And they’re painting the walls black,

The circus has a show today,

But there are no tickets to it.

Ведут слепого коммиссара,

Похоже он учуял след.

Одна рука торчит в кармане,

Другая держит пистолет.

It looks like he’s sniffing the trail,

One hand is in his pocket,

The other is holding his pistol.

А толпа опять бушует,

Её сегодня тянет вдаль,

Пока Леди и я глядим в окно

На улицу Печаль.

And the crowd is restless again,

Today the far beyond beckons to them,

While Lady and I look through the window

Onto the Street of Sadness.

Золушка спокойно,

С улыбкой скажет: "Не беда.

Пройти всем в жизни надо

Через отчаянья года".

Cinderella calmly

With a smile says “No problem.

You must experience everything in life

Through the reckless years.”

Тут вдруг врывается Ромео.

"Ты же моя!", он в плач и в крик.

Ему ответит кто-то тихо:

"Ты не туда попал, старик".

Then suddenly Romeo bursts in,

“You are mine!” with a cry and a scream.

Someone quietly answers him:

“You’re in the wrong place, old man.”

А потом сирены стихнут

И только Золушка одна

Метёт обрывки старых писем

На улице Вина.

And then the sirens fall silent,

And just Cinderella all alone,

Sweeps up scraps of old letters

On the street of guilt.

Сейчас луны почти не видно

И звёзды спрятались давно.

Даже старая гадалка

Закрыла наглухо окно.

Now the moon is almost not visible

And the stars were hidden long ago.

Even the old fortune teller

Has closed her window tight.

Все, кроме Каина и Брата

И попрошайки с Пляс де Вож,

Все занимаются любовью

Иль просто ожидают дождь.

Everyone but Cain and his brother

And the beggar of the Place des Vosges,

Are all making love

Or just expecting rain.

А Филантроп принарядился,

Набил бумагою карман.

Он - главный гость на карнавале

На улице Обман.

But the philanthropist is all dressed up,

And stuffed his pocket with paper.

He’s the main guest at the carnival

On the Street of Deceit.

Вот Офелья, за неё мне страшно.

В её сердце - пустота.

Как скоро её cломала

Повседневная суета.

There’s Ophelia, I’m so afraid for her,

In her heart is emptiness.

So soon she was beaten down

By the cares of everyday life.

Смерть ей кажется прекрасной,

Hа груди - бронежилет.

Она стала старой девой

В свои юные двадцать лет.

Death seems wonderful to her,

She wears an armor breastplate

She’s turned into an old maid

At the tender age of 20 years.

И хотя во снах рисует

Цвета радуги вновь и вновь,

Из засады швыряет камни

На улицу Любовь.

Although in dreams she paints

The colors of the rainbow over and over,

From her ambush she throws stones

Into the Street of Love.

Эйнштейн в костюме Робин Гуда

Проходил недавно тут.

Вслед чемодан воспоминаний

Тянул его товарищ Шут.

Einstein disguised as Robin Hood

Passed here not long ago.

After him his suitcase of memories

Was pulled by his comrade Clown.

Швырнул так зло он сигарету,

Как будто это - динамит,

Потом пошёл, шатаясь, дальше,

Читая громко алфавит.

He flung his cigarette so wickedly,

As if it was dynamite,

Then he passed on, staggering,

Loudly reciting the alphabet.

Быть может, ты его не помнишь,

Он был когда-то виртуоз

Игры на электронной скрипке

На переулке Грёз.

Maybe you don’t remember him,

He was once a virtuoso

Playing the electric violin

In the Alley of Visions.

Доктор Фильц содержит судьбы

На дне огромных сундуков,

Каждый его подопечный

Ищет ключи от замков.

Doctor Filtz holds our destinies

In the bottom of huge trunks.

Every one he watches over

Is seeking the keys to the locks.

Mедсестра, та что в ответе

За цианкалий и за грог,

Ведёт ночами картотеку

С названием "Храни их, Бог".

The nurse that is in charge

Of the potassium cyanide and grog,

Carries the file of cards

Inscribed “God protect them.”

Они оба играют на дудках,

Ты услышишь их чудный дуэт,

Если высунешь ухо подальше

Из окна на улице Бред.

They both play on fifes,

You hear their wondrous duet,

If you stick your ear out the window

To the Street of Delerium.

Напротив шторы закрыты,

Там ужин готовят наспех,

Казанову кормят надеждой

На скорый у женщин успех.

On the other side the shades are drawn

They’re hurredly preparing dinner there.

They are feeding Casanova the hope

Of easy success with women.

Они в нём воспитают

Непомерную гордость собой,

А назавтра удачей отравят,

Смешав сладкий яд с похвалой.

In him they are nurturing

Boundless pride in himself,

But tomorrow they’ll poison him with success,

Having mixed sweet poison with praise.

А Фантом кричит в катакомбах:

"Казанове урок будет пусть,

Как ходить вечерами украдкой

На улицу Вечная Грусть".

And the phantom shouts in the catacombs:

“Let Casanova learn his lesson

For secretly going in the evenings

To the Street of Eternal Sorrow.”

Ровно в полночь все агенты

Из спецотряда сверхлюдей

Стучатся в двери тех, кто полон

Различных мыслей и идей.

At the stroke of midnight all the agents

From the supermen’s special brigade

Knock on the doors of those who are full

Of various thoughts and ideas.

Потом они везут их в замок,

Где подключают аппарат

Сердечных приступов к груди им:

Никто не будет виноват.

Then they take them to the castle

Where they hook up to their chests

The heart-attack machine:

No one will guilty.

Команда страховых агентов

Стоит с канистрами в руках.

Их цель: Предотвращать побеги

На улицу Забытый страх.

A crew of insurance agents

Stand with canisters in their hands.

Their job is to prevent escapes

To the Street of Forgotten Fear.

Слава Нептуну Нерона!

"Титаник" плывёт по волне,

Hа палубе все ещё спорят,

Кто был на чьей стороне.

Praise to Nero’s Neptune!

The Titanic sails over the waves,

On the deck everyone still argues,

Who was on who’s side.

Taм Эзра Паунд и Ти Эс Эльотт

Ведут на мостиke дуэль,

Над ними смеётся Калипсо

Под нежную песнь Ариэль.

There Ezra Pound and TS Elliott

Are fighting a duel on the bridge,

Calypso is laughing over them

Under the tender song of Ariel.

Ведь только там, в глубинах моря,

Где благодать и красота,

Нет смысла думать слишком много

Об улице Dreams.

It’s only there, in the depths of the sea

Where there is abundance and beauty,

There is no reason to think to much

About the Street of Dreams.

Я получил твоё письмо,

Получил ещё вчера.

Ты удачно пошутил,

Спросив, как мои дела.

I received your letter,

I got it already yesterday.

You made a good joke,

Asking how I was doing.

Всех, о ком ты пишешь мне,

Я знаю их, их жизнь скучна,

Я изменил их лица,

Дал им другие имена.

Everyone that you wrote me about,

I know them, I’m tired of their lives,

I changed all their faces

And gave them different names.

Теперь я не могу читать,

Не пиши же мне, пока

Не переедешь, как и я,

На улицу Тоска.

Right now I can’t read,

Don’t write to me until

You cross over, like me,

To the Street of Grief.

Sunday, February 3, 2008

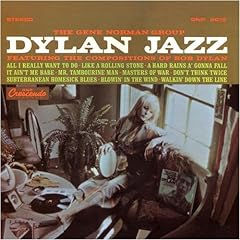

Dylan Jazz....

Lost in piles of budget exploitation records, Glen Campbell meets Bob Dylan and makes a gem of an album that’s not going to see a CD reissue anytime soon.

Back in the early ‘70s, I wasn’t in the mood for guys singing about rhinestone cowboys or Wichita linemen, especially with full orchestras and background singers. It was a time of very serious artists with serious acoustic guitars who played mostly unaccompanied and always wrote their own serious songs (how could you sing about feelings that weren’t your own?).

Dave was this banjo-playing bartender friend of mine who let me drink for free in a dark roadside motel bar just outside of the town I was living in at the time. I kept him company and watched him win hundreds of dollars from road-weary truck drivers with his “red card, black card E.S.P.” card trick that, countless beers and truckers later, I finally figured out how to do. Late one evening at his apartment somehow Glen Campbell’s name came up in a conversation and I sneered and made some comment about "rhinestone linemen." A little later he put on a record and said, “Listen to this.” It was some bluegrass track and in the middle was a totally monster mandolin solo.

“Holy smokes!” I said. “Who’s that mandolin player?”

“That isn’t a mandolin player.” My friend said. “That’s Glen Campbell on a 12-string.”

While I didn’t become a fan at the time, that was later after I realized that Jimmy Webb was a genius, I did stop sneering and developed a respect for Campbell, Tommy Tedesco, Howard Roberts, Hank Garland and another hundred faceless session musicians I’ve learned about over the years.

If you ever see The Monkees video for “Valerie,” notice how the camera cuts from a wide shot of the whole band to a super tight close up of the hand on the fret board of Mike Nesmith’s Gretsch White Falcon guitar during the solo. If I had a favorite Monkee it would be Mike, no doubt. His solo material is really quite good. But the guitar solo in “Valerie” is about as beyond his abilities as a guitarist as James Joyce’s “Ulysses” is beyond mine as a writer (or a reader for that matter). If you could see the arm attached to that hand it’d be attached to Glen Campbell [*actually, it turns out that's an internet legend; the guitarist is really session legend, Louis Shelton].

As the rules of irony might dictate, during the Glen Campbell scorning period of my life my musical idol was Bob Dylan. It was Dylan after all who turned the definition of folk “authenticity” on its head and in the wake of his work nobody was authentic if they weren’t singing their own songs (and another strike against the Rhinestone Cowpoke).

Where the irony enters is in the form of this album, Dylan Jazz. An album of Dylan songs done instrumentally in small jazz-combo arrangements by the Gene Norman Group and lifted up into someplace special by the guitar playing of Glen Campbell.

The GNP Cresendo label was the creation of Gene Norman, whose jazz club, The Crescendo, was a famous Sunset Strip nightclub in the 1940s and ‘50s and home to performances by every major jazz artist of that era. Gene Norman started his GNP label in 1954 and later struck gold with releases of Star Trek and Trek-related albums. Gene Norman told me the funniest joke I ever heard.

I met him in his hotel room at a NARM convention in San Francisco about six or so years back. He was in his late-70s and sat on the edge of his bed smoking a huge cigar.

“I heard a good joke the other day.”

There was a theatrically long pause for effect.

“I met a man who didn’t own a record label.”

You can’t see me but I’m still laughing almost too hard to type.

Gene showed me his passport. Where it has occupation listed his had, “Impresario.” I still think it was among the coolest things I've ever seen.

Needless to say, Gene is relegated to playing the electric cash register in “The Gene Norman Group.” The musicians here are Jim Horn on sax and flute, Glen Campbell on guitar, Al Delory on piano, Lyle Ritz on bass, and the great Hal Blain on drums. The album was produced by Leon Russell and Snuff Garrett and sounds like everyone involved had a pretty good time in the process.

The sleeve here is a surprisingly hip quotation of the sleeve of Dylan’s 1965 LP “Bringing It All Back Home.” An issue of Time magazine lies on the table by a harmonica. The woman sits by an acoustic guitar and holds a tambourine. The covers of two older Dylan LPs are to the bottom right, the top of his 1962 debut record just peeking into the frame.I have a fatal weakness for guitar players, a fact well illustrated by the leaning tower of record crates across the room, and this is one wonderful jazz guitar album.

Most tracks are only briefly recognizable during an opening passage where the melody line can be heard, then take off into some terrific flights of fancy mostly via Campbell’s outrageous guitar playing. My friend, Scott Ballentine, is one of the better guitar players in Indianapolis, and his taste in guitar music is pretty brutal. I’ve never come up with a favorite airy arty solo finger-style acoustic guitar record that he didn’t ridicule within the first 10 or 11 seconds. Some of my all-time favorite guitar players, such as Larry Coryell and Lenny Breau, don’t rate much above a begrudgingly mumbled “Mmmm yeah, they’re OK.” It has become my mission to find guitar records that slap that “show me something” smile off his face, and I am happy to say that this one left both cheeks stinging.

Scott, like me but even more so, is not dazzled by shows of technical virtuosity alone. There’s got to be somebody there. There’s got to some feeling, some heart, some soul in the notes and in the spaces between the notes or it’s just not going to be worth going back to a second and third time.

Dylan Jazz is stuffed full of spirit, heart, soul, whatever you want to call it. A good deal of it flows from Glen Campbell’s fingers on the lesser-known “Walkin’ Down the Line,” in particular. Songs that are musically a bit on the monotonic side like “Masters of War” and “A Hard Rains A’ Gonna Fall,” are opened up melodically wider than I might have thought possible.

I’ve collected Dylan LPs for over 20 years and have never come across this until Punkin Holler Boy, John Sheets, gave me an old beat up copy he had lying around. I just slightly upgraded that one, courtesy of eBay, but still kick myself over a German pressing on the Vogue label I missed about a month or two back. The first time I saw Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music on CD I realized that just about anything might come out on disc eventually, but I’m not holding my breath waiting for this one. However, I was surprised as all get out to just now find that the album is available from iTunes as a download.

Saturday, December 8, 2007

I'm Not There....

Restored to bright and vibrant color, The Beatles second film, Help!, has just been reissued on DVD. I bought a copy a week or two before I saw the new Todd Haynes Bob Dylan anti-biopic I’m Not There. I mention the two films together because I remembered that among the ideas kicked around for the third Beatles film was one that called for the four Beatles to play four different aspects of one character. At one point the Italian director Michelangelo Antonioni was supposedly connected to the idea – most likely apocryphal given that Blow Up is the most critical film even made about “the sixties” generation – but nothing ever came of it.

Without question however, the most bizarre third Beatles film that never happened involved a plan to have Stanley Kubrick direct the four Beatles in a film version of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings with George as Gandalf, Paul as Frodo, Ringo as Sam, and John as Gollum.

Dennis O’Dell, the head of Apple Films had worked with Kubrick on the production of Doctor Strangelove. In The Beatles film Magical Mystery Tour (which I think represents a home movie more than a follow-up to Help!) there is a sequence for the lone Beatles’ instrumental “Flying” in which O’Dell took some aerial footage shot for Doctor Strangelove but never used, and colorized it, giving it a sufficiently psychedelic look. Amazingly, when the film debuted on British TV on Boxing Day 1967, Kubrick watched it at home, recognized his pilfered footage and called O’Dell.

Around the same time someone gave John Lennon a set of the Tolkien books which he read during those moments when the acid wore off long enough for the letters to stop swirling around the page. Needless to say, John was hooked. O’Dell took the idea of a Beatles’ Lord of the Rings to United Artists who said they were interested, but because of what would be a sizable budget, required that a “name” director be part of the deal.

You can see where this is going.

O’Dell met with Kubrick who said he was interested but that he’d never read the Tolkien books. Stanley had booked passage on a ship back to the US and said he would read them on the trip. When he returned he called O’Dell and announced that the books were quite good but completely unfilmable and bowed out of the discussion. By that time Lennon’s attention had already moved on to the next batch of shiny bright things and the idea was quietly abandoned.

I love this story because it reminds me of something I can easily forget when I listen to The Beatles. By the time the band was reduced to nothing more than a room full of lawyers in 1970-71 not a single Beatle had yet turned thirty years old. The idea of the four of them tripping their way across Middle Earth is the perfect LSD-fueled fantasy of twenty-something young men.

But I digress….

Before I tell you what I think about I’m Not There, let me say that I think you should see it. Unlike most films playing as I write this, it’s worth your time.

I don’t believe you have to be a "fan" of Bob Dylan to see this film.

Dylan occupies a place in the culture comparable to the one occupied by The Beatles. A person who owns no Beatles albums, who would fail a “name that tune” round of Beatles songs, who might not even be able to successfully match “John “Paul” George” “Ringo” to the four photos that came with The White Album, would still have absorbed enough information about The Beatles through his skin in the process of walking through the world by this point to watch a documentary on The Beatles and make sense of it.

The idea here was to not make the standard biopic in which the actor playing the “young Bob” would have some conversation with his mother in their Hibbing, Minnesota kitchen over oatmeal about following one’s dream before a slow dissolve turned him into the actor playing the “older” Bob walking up the steps of the Brooklyn State Hospital on his way to meet Woody Guthrie.

If that sounds like a film you’d like to watch, well, WHAT THE HELL IS YOUR PROBLEM?!?!?

Sorry. I just hate “biopics.”

And where I’m Not There develops problems is in the degree to which it actually fails to escape the gravitational pull of the standard biopic for all it’s cleverness in casting six actors to play Bob Dylan.

Among the most interesting portrayals is one by the young 11 year-old African-American actor, Marcus Carl Franklin, as “Woody Guthrie.”

Before single-handedly forcing a redefinition of “authenticity” in folk music by the sheer power of his will and talent, Bob Dylan entered the stream of the folk revival understanding (1) that there were “authentic” lives and (2) that his wasn’t one of them. What an odd notion, that authentic people could never be Jews from Minnesota whose fathers owned appliance stores.

Bob Dylan would have never survived in the media culture of 2007.

Having developed a reputation as an engaging performer with albeit limited appeal, he’d lucked out and gotten a good review in the NY Times that brought him to the attention of John Hammond, Sr. who signed him to Columbia and produced a debut LP that sold fewer copies than any record in Columbia’s history. It was when he began to write that he began to attract an audience.

Befriended by the reigning Queen of Folk Music, Joan Baez, Dylan wrote “Blowing in the Wind” a song that, totally unlike the rest of his massive catalog, resembles “Amazing Grace” and “We Shall Overcome,” songs that sound as if they have no authorship, as if they were delivered on stone tablets or first heard rising from a burning bush.

But Robert Allen Zimmerman from Hibbing, Minnesota, had crafted a fictitious biography for himself. His parents were dead, or had been carnival folk, or both. He was raised in a traveling carnival that roamed across the southwest, or by wolves in South Dakota. He learned songs first hand at the knee of Blind Snake Oil Roberts and Old Sorrowful and Lightning Hopkins and Blind Boy Fuller.

One of the best bootleg recordings of early Bob Dylan is a radio program called “Folksinger’s Choice” hosted by Cynthia Gooding which aired in New York sometime in 1962 (I have seen both November and March dates listed). Dylan performs fourteen songs, a mix of early originals, traditional songs, and songs by Hank Williams, Bukka White, Howlin’ Wolf and Woody Guthrie. The performance is incredible, but the interview, also extensive, is amazing. If Gooding had asked Dylan his belt size, the date or the time I am certain he’d have lied about those too!

CG: When I first heard Bob Dylan it was, I think, about three years ago in Minneapolis, and at that time you were thinking of being a rock and roll singer weren't you?

BD: Well at that time I was just sort of doin' nothin'. I was there.

CG: Well, you were studying.

BD: I was working, I guess. l was making pretend I was going to school out there. I'd just come there from South Dakota. That was about three years ago?

CG: Yeah.?

BD: Yeah, I'd come there from Sioux Falls. That was only about the place you didn't have to go too far to find the Mississippi River. It runs right through the town you know. (laughs).

When I say that Dylan wouldn’t have survived the media climate of 2007 I mean that the story that broke sometime in, I think, 1964 in which a reporter tracked down Dylan’s (still living) parents and his High School year book photo played out fairly quickly. Dylan mostly refused to comment on it and the world moved on. A world that didn’t have 300 24-hour cable news channels looking for “stories.” In today’s world, Dylan could have easily been tarred as the Vanilla Ice of the folk revival.

I suspect that after the interview Dylan went home with Gooding, stayed for a couple weeks, ate all her food, stole her record collection and moved on.

I’m not joking about the record collection either. The young Bob Dylan was one of the original “turn table artists.” Until Dylan’s generation, musicians learned their craft at the feet of other musicians who came before them. Ramblin’ Jack Elliot (a Jew from Brooklyn born one Elliott Charles Adnopoz in 1931) really did run away from home and join a rodeo and learn his first guitar chords from a rodeo clown. Jack heard Woody Guthrie, tracked him down and traveled with him throughout the western US for years learning his craft.

But Dylan, like almost everyone who followed him, would learn his craft on the edge of a bed sitting by a turntable playing records, sometimes slowing them down to figure out guitar parts. Among the stories told about Dylan’s early days in New York is one about his theft of a stack of records from someone who’d been nice enough to offer his couch and the friends of that guy who showed up one night intent on retrieving the records and putting a beating on the voice of their generation.

One of the purloined records was the Rosetta Stone of the folk revival, Harry Smith’s Anthology of American Folk Music. A compilation of recordings of American folk and country music commercially released as 78 rpm records between 1927 and 1932, the anthology was released in 1952 on Folkways Records as three two-LP sets. This was the document that brought the works of Blind Lemon Jefferson, Mississippi John Hurt, Dick Justice, The Carter Family and Clarence Ashley to the attention of this new generation of performers. In the liner notes to the 1997 reissue, the late Dave van Ronk wrote that "we all knew every word of every song on it, including the ones we hated.”

As early as 1927, Carl Sandburg understood that “A song is a role. The singer acts a part . . . all good artists study a song and live with it before performing it . . . . There is something authentic about any person’s way of giving a song which has been known, lived with and loved, for many years, by the singer.”

Robert Cantwell, in his book When We Were Good: The Folk Revival, writes that by 1965 “the folksinger’s persona had evolved into a loosely conventional form, that of the casually road-weary traveler in jeans and boots or peasant frocks, clothes rumpled as parents would allow, erratic hair, one who speaks a pidgin idiom neither south nor west but vaguely regional and proletarian, that non-regional dialect of the Shangri-La West that Bob Dylan and Jack Elliot hailed from, that mythical nowhere where all men talk like Woody Guthrie and are recorded by Moses Asch.” (pp. 328-329)

“Whoever Bob Dylan was, Columbia’s high-fidelity micro-grooves brought his callow voice, wretchedly overwrought, his stagey panhandle dialect, his untutored guitar and harmonica – all of his gallant fraudulence – into dormitory rooms with shocking immediacy. And when, in the spoken preface to his shattering ‘Baby Let Me Follow You Down,’ he waggishly reported that he had learned the song from one Rick Von Schmidt, a blues guitar player from Cambridge, whom he had ‘met one day in the green pastures of. . .ah. . .Harvard University,’ the folk revival had met one of its own.” (p. 345)

“The folk revival, then, is really a moment of transformation in which an unprecedented convergence of postwar economics and demographic forces carried a culture of personal rebellion across normally impermeable social and cultural barriers under the influence of authority of folk music, at once democratic and esoteric, already obscurely imbued with a spirit of protest. This passage across social lines, again, transformed it, endowing it with new expressive forms, and with a legitimacy both wonderful and terrible – terrible because the massively politicizing issue of the Vietnam War, beginning in 1965, would swell it to a tidal wave of protest that swept destructively over the cultural landscape, leaving behind it deep racial, class, gender, and other moraines.” (p. 346)

By 1965 Dylan’s emerging persona became the source of a self-contained “authentic” self. The more other songwriters scrambled to write “Bob Dylan” songs, the more authentic Bob Dylan became in contrast.

But, I digress….

Pretty much everything above lies in the subtext of Marcus Carl Franklin performance as “Woody.” Later in the film, in the odd and disjointed old western town of “Riddle,” Franklin reappears dressed as Charlie Chaplin with Chaplin moustache and cap and cane, only for a moment before disappearing back into, well, the “Riddle.”

Haynes says there was a seventh Dylan in the original screenplay, a Chaplin character created to represent the Dylan of the folk coffeehouse scene in New York whose performances were – and people just coming to Dylan today will find this incomprehensible – funny. But the character was cut for length, and length is the other problem I think the film suffers from. Just as Chaplin Dylan was reduced to a cameo, I think dropping the lion's share of Ben Whishaw’s Arthur Rimbaud Dylan could have helped the problem of the film’s length.

In a traditional narrative, there is a feeling you get as a story proceeds; a sense of where you are – beginning, middle or end – at any point. When a film that really tells no story is long, the feeling that this may never end is not a particularly pleasant one. Cutting most of the Rimbaud Dylan and trimming the Woody Dylan – what’s up with the big whale in the river anyway? – would have been a good step in cutting some length.

Walking out of the theatre, I wasn't sure what to make of Christian Bale’s performance as both the Protest Dylan and Gospel Dylan. After a few days of letting them resonate, I think he does a superb job of playing a man who is more uncomfortable in his own skin than anyone I think I’ve ever seen.

It’s here where a mini tsunami of Dylan iconography is unleashed in the form of famous photos, still images that spring to life, concert posters, and a spot-on perfect performance by Julianne Moore as Joan Baez. I’m not sure it’s even possible to explain how impressive her performance is to someone unfamiliar with the various stages of Baez. The Bale/Jack Rollins/Protest Dylan is, at times, uncomfortable to watch which is, I think, the point.

Bale’s later transition into the Gospel Dylan is extraordinary as well. Here again we get the underlying shift in the Dylan persona, done in a way that side-steps the standard biopic very well. This Rollins/Dylan is an ordained minister. Unlike the “real” Dylan, this Dylan never came back from his conversion, and in the end is reduced to preaching a dire “last days” message to a room of maybe 8 people. The fact that he even plays music seems inconsequential.

The film has a point of view - it doesn't like this apocalyptic evangelical variant of Christianity. It is very clear on this point.

What Haynes has done with Heath Ledger’s Robbie the Actor Dylan – who we first see as he becomes famous for his portrayal of the Jack Rollins/Protest Dylan in a “biopic” is, along with the idea of the Woody Dylan, to create the most successful attempt to fracture, shatter, and generally screw with traditional biopic conventions.

Of all the Dylans here, Ledger’s looks more like the Woodstock-Self Portrait-era Bob than even Blanchett does the 65-66 Bob. And Ledger performance is aided enormously by Charlotte Gainsbourg playing a character assembled from biographical bits of Suze Rotolo and Sarah Lowndes-Dylan made into a French painter. In offering this next-to-impossible-to-sort-out jumble of truth and fiction Haynes simultaneously gives us the “real” (i.e., unreal) “Bob Dylan” and shines a light on new directions in the biopic. For me, these are the peak performances in the film.

I’ve read one criticism of the push for a “Best Actress” Oscar for Cate Blanchett that argues that she only merits “Best Supporting Actress” because she plays the same part played by five other actors in the same film. This sounds like it was written by someone who read a synopsis but hasn’t actually seen the film; Blanchett’s “Jude Quinn” (I don’t know either, maybe some weird weld of “Hey Jude” and “Quinn the Eskimo”) totally dominates the movie. She has more screen time and the combination of her skills – she is the “best actor” here – and the unavoidable novelty of casting – like Travolta in Hairspray ratcheted up by the power of ten – allow her to, at times, disappear into the part.

But it is in these sequences, shot in black & white so as to resemble D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back, that I’m Not There downshifts into an almost conventional biopic mode. We get great performances by David Cross as Alan Ginsberg and Peter Friedman as Albert Grossman/Morris Bernstein and Bruce Greenwood as the journalist-cum-inquisitor/Mister Jones/Pat Garrett. We even get the Bobby Neuwirth-Bob Dylan-Edie Sedgwick (“Co-Co Rivington”) love triangle. The Jude Dylan sequence comes closest to the “dumping the notebook” phenomenon in which Haynes finds so many period factoids so interesting that he seems to squeeze one in at every opportunity.

The scene that almost saves this sequence is the meeting by the river where Dylan arrives with The Beatles in an explosion of the visual comedic style of A Hard Day’s Night as they tumble and roll on the grass. The four exit through the gate to the rear, first herded to the left by a bowler hat-wearing Brian Epstein, to remerge in the background a moment later running to the right chased by a small crowd of screaming fans. As Jude Dylan enters he is immediately waylaid by Max Walker playing a perfect collection of tics that comprise every fact-obsessed Bob Dylan “fan.” This was the one moment I laughed out loud in the theatre.

Haynes' intent seems most obscure in the film's last sequence with Richard Gere as a Billy the Kid Dylan living quietly in the old western town of Riddle. The Charlie Chaplin Dylan makes his brief appearance here, a band plays "Goin' To Acapulco" and the visual style of the cover of The Basement Tapes album is heavily referenced in the various characters and still life's on display. Modernity is about to destroy the old ways of the town; when Billy Dylan protests, an ancient Pat Garrett imprisons him. He escapes and hops a freight train heading out of town where he finds Woody's guitar, dusts it off and strums as he watches his dog run after the train but not quite make it.

That last bit, Dylan abandoning the dog rather than jumping off, getting the dog, and catching the next train I read as Haynes' quiet little reference to what a self-centered jerk the "real" Bob Dylan is, cutting off friends and lovers and never looking back. One person I discussed the film with saw it more as a reference to sacrifice, but it seems more like the dog's sacrifice than Bob's so I'm not sure what that means.

The whole Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid period is a minor footnote in Dylan's biography and I'm not really sure why it's elevated to play the role it does here. Nor am I clear on why Dylan, who played a character named "Alias" in the Peckinpah film, is recast now as one of the leads. The entire Billy the Kid Dylan sequence has this other narrative imposed upon it with its own characters and its own drama, but the drama is more dream-like than anything else. The sort of dream you have that makes perfect sense until you slowly wake up, your rational mind kicks in, and all the "sense" your dream made blows away like so much smoke.

The "sense" to be found in Dylan's best work is more like that dream sense; a kind of non-rational connect-the-dots of imagery and the play of language across the surface of the texts (think "Visions of Johanna" "Desolation Row"). So it is with most of this film; and that may well point to a fundamental structuring device here as one of a series of dreams.

In the end, it is the longest sequence, the only black & white sequence, the one that everyone who will write about this film will write about - as if the casting of Cate Blanchett to play the androgynous Dylan of 65-66 is somehow more novel than casting an 11 year-old black actor to play the 20 year-old Dylan - is the one that comes most dangerously close to the very film Haynes set out not to make.

Monday, November 5, 2007

Masked and Anonymous....

Every so often I get into an argument over this 2003 film by Larry Charles. Since I am a fan of Bob Dylan I am accused of having my judgement clouded. I am accused of not being able to distinguish between a film that I "like" and a film that is "good." As I have been known to spend hours explaining why I think Pootie Tang is infinitely superior to American Beauty I recognize that this is a self-inflicted wound.

Every so often I get into an argument over this 2003 film by Larry Charles. Since I am a fan of Bob Dylan I am accused of having my judgement clouded. I am accused of not being able to distinguish between a film that I "like" and a film that is "good." As I have been known to spend hours explaining why I think Pootie Tang is infinitely superior to American Beauty I recognize that this is a self-inflicted wound.But this is not the case here. I will often explain how my wife, who is not a fan of Dylan in particular, has become a major fan of this film. When people she doesn't know come to visit she often shows them the film and, if they react like a typical movie critic (who until a week ago was reviewing restaurants) that's the last we'll see of her that evening. And, while I have never called this film a "masterpiece," I do believe it is better by far than the vast majority of the films that are lavashied with awards at what has come to represent the dark side of the force in independent film - Sundance.

Whenever I have to mount a defense of the film I am always sent back to the internet and a Google search for what I think is the most cogently argued defense I've ever read. Written by David Vest in the 20 September 2003 issue of CounterPunch, "Masked and Anonymous: Dylan's Elegy for Lost America" says everything that I could hope to say about the film. Rather than have to go look for it everytime I need it I've decided to archive it here. if you haven't seen the film check your library's database immediately. Here's the trailer to tide you over.

Bob Dylan's new film, "Masked and Anonymous," has met with almost universal condemnation (or worse, condescension) from critics in the corporate media. According to most reviewers, in lieu of a plot the film offers "rambling incoherence" and "incomprehensible dialogue." It is "an exercise in self-indulgence." Several reviewers have actually worried in print that Dylan made the movie in order to have some kind of joke at their expense. Dylan's character, Jack Fate, has little or nothing to say, we are repeatedly told, and more or less just "sits there like a toad," in the words of Roger Ebert, who should be the last person to accuse anyone of that.

Could the movie really be this bad? It wouldn't matter if it were equal to "The Tempest" or "Julius Caesar," it has already been pronounced D.O.A.

Anytime the nation's media are this unanimous about anything, one would do well to be suspicious. After all, President Bush's decision to invade Iraq in search of "weapons of mass destruction" was met not with skepticism but with near-unanimous cheerleading and boosterizing in the corporate media.

Reviewers had already effectively killed Dylan's film by the time it arrived in Portland, Oregon for a perfunctory one-week run. Although attendance grew steadily during the week, it started sparse and grew toward respectable.

Not ten minutes after the opening credits I could see why the film had been marked for assassination by big newspaper media critics. They are the villains of the piece! "Masked and Anonymous" portrays the reporters who wrote the bad reviews as people who have to wear ankle monitors. Editors hold the keys that control them. Who owns the editors is pretty clear, too. The sight of superstar critic and Sixties specialist "Tom Friend" (Jeff Bridges) being beaten to death with Blind Lemon Jefferson's guitar must have been too much for them.

"Friend," obsessed with his own memories of the Sixties but oblivious to what is going on outside the window, never seems to notice that Fate, his quarry, answers none of his questions.

Officials of the "network" televising the "benefit" on which Fate is to appear see him as self-indulgent, too. They want him to sing "Jailhouse Rock," "Jumping Jack Flash" and "Revolution - the slow version."

He gives them "Dixie."

The infamous "rambling and incomprehensible" plot is in fact rather well-constructed and makes abundant sense. Although the project could have used some tighter editing and more attention to minor issues of continuity, anyone who couldn't follow this movie probably couldn't be trusted with a comic book. The storyline is no more "obscure" or "disjointed" than "A Hard Day's Night."

But it hits a great deal harder. When the camera pans slowly down a desolate L.A. avenue, and Dylan is heard singing "Seen the arrow on the doorpost, saying This Land is Condemned, all the way from New Orleans to Jerusalem," try to keep tears from welling. (Or sit there like a toad eating popcorn and stuff the feeling, it's your call.)

Whereas the concert finale of "A Hard Day's Night" is witnessed by screaming teenagers and an adoring TV audience, the concert performed by Fate in "Masked and Anonymous" is seen by no one except stage hands and extras because it is pre-empted by a presidential speech and interrupted by guns and bayonets.

In spite of what you may have read, the film is not "set in some imaginary third-world country at some point in the future," anymore than King Lear is about prehistoric England. Failure to recognize the true setting should immediately disqualify any reviewer. "Masked and Anonymous" is a spot-on accurate portrayal of what is going on RIGHT NOW, seen through the eyes of someone with vision and not just eyesight, someone who has looked through the eyes not only of Charley Patton and Elizabeth Cotton but also of Emmett Miller and even Daniel Decatur Emmett.

All America's chicken-hawk foreign wars have come home to roost. The horrors once visited upon El Salvador, Nicaragua, Vietnam, Somalia and Iraq are now rolling through the streets of California. All the electoral disgrace of recent campaigns has been compressed into one presidential speech. As for the major media as portrayed in this film, it is impossible not to think of Christiane Amanpour's recent admission that CNN "was intimidated" by the Bush administration and operated in a "climate of fear and self-censorship" during the invasion of Iraq.

When the new president (Mickey Roarke) concludes his "war-is-peace" oration at the end of the film with the sarcastic words "May God help you all," it is merely what anyone with a perceptive imagination can hear Bush or Cheney saying when they conclude their speeches with the formulaic "God Bless America." Certainly the administration portrayed in "Masked and Anonymous" is no more thuggish than the one currently rooting at the trough in Washington.

Or, as Uncle Sweetheart (John Goodman) puts it, "It's the dark princes, the democratic republicans, working for a barbarian who can scarcely spell his own name."

When a soldier (Giovanni Ribisi) tells Fate of fighting first with the rebels, then with the counter-insurgents, then with the Government, then with the rebels again, only to discover that some of the rebels are in fact funded by the very Government they're supposed to be opposing, how strange does that seem to anyone familiar with the betrayals and capitulations of contemporary politics, especially movement politics? It's like finding out who sponsors "Earth Day."

My favorite exchange: "I'm trying to be on your side, Jack," says Uncle Sweetheart, the promoter who is, naturally, "only trying to help."

"You have to be born on my side, Sweetheart," says Fate.

To be on the side of workers, of animals, of oppressed people, of love, of the truth is to court destruction. Before singing his final song and meeting his own fate, Jack Fate experiences a visitation by his ghostly forerunner, Oscar Vogel (Ed Harris), a banjo-playing entertainer who worked in blackface and who disappeared after raising his voice against the times. When Fate looks back to catch a last glimpse of Vogel, the vaudevillian has been replaced by a young Black man who could be a janitor, a Reggae artist or a rising Hip-Hop truth teller, next in the line of destiny, or line of fire.

This film isn't perfect. I have read the original screenplay and far too much has been cut out of it to try to make it acceptable to people who would have had none of it under any circumstances. But it is the only motion picture I have seen so far in this millennium that seems to have a clue about what is going on in America. Moviegoers will get it or they won't. Great pains have been taken to ensure that they won't even see it.

It is a tale of almost unbearable sadness and loss. When Dylan sings "I'll Remember You," as electrifying a performance as has ever been caught on camera (all the songs are performed live, there's no lip-synching in this movie) you feel that he may well be singing not merely about a person but also about that "lost America of love" that Ginsberg mourned in "A Supermarket in California," a work that in its visionary aspect and intensity "Masked and Anonymous" resembles. (Its ultimate antecedents are of course Shakespeare's history plays.)

When Dylan's character, Fate, is reunited with his lost/doomed love (Angela Bassett, magnificent in the role), she endeavors with great tenderness to console him for his losses, and without a word Dylan manages to convey that Fate's grief is inconsolable. It is a scene of considerable beauty and delicacy.

Dylan's performance has been called "inscrutable." But who else could have played this role? There are people who find his songs inscrutable as well, and I suppose arguing with them would be as pointless as trying to answer "Tom Friend's" interview questions. (These days, anything an idiot can't or won't bother to understand is "incomprehensible" and "inscrutable.")

The most daring (and intriguing) line in the film slips by almost unnoticed: moments after Jack Fate is arrested for a sudden act of violence committed by his sidekick Bobby Cupid (Luke Wilson), he thinks to himself, "Sometimes it's not enough to know the meaning of things. Sometimes we have to know what things don't mean as well. Like, what does it mean to not know what the person you love is capable of?"

Unlike D. A. Pennebaker's "Don't Look Back," which showed a young Dylan eating dumb but presumptuous critics alive, "Masked and Anonymous" depicts an aging Jack Fate with nothing whatever to say to them. "I was always a singer and maybe no more than that," he says.

So much for "self-indulgence."

Friday, October 19, 2007

December 7, 1997 and August 28, 1963

I'm sure there are other reasons these dates are significant, but I find them interesting because on both days Bob Dylan hung out a bit with Charlton Heston.

I'm sure there are other reasons these dates are significant, but I find them interesting because on both days Bob Dylan hung out a bit with Charlton Heston.Now, not to dive into the deep end of French literary theory but one favorite distinction gleaned from that work was Roland Barthes' notion of the writerly and readerly texts. Put simply, the meaning in readerly texts is fixed and rigid, but in writerly texts the meaning is more fluid, more open. Barthes said "In readerly texts the signifiers march; in writerly texts, they dance." As artists, the difference between Bob and Chuck seems pretty clear.

In 1997, Dylan and Heston were in the group of five artists honored by President Clinton at The Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. In 1968, both men were also together in Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and a quarter of a million men and women marching together for social justice.

The March on Washington represented a coalition of several civil rights organizations, all of which generally had different approaches and different agendas. The "Big Six" organizers were James Farmer, of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE); Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); John Lewis, of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC); A. Philip Randolph, of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters; Roy Wilkins, of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); and Whitney Young, Jr., of the National Urban League.

Opposition to the march came from a number of quarters. President Kennedy originally discouraged the march, for fear that it might make the legislature vote against civil rights laws in reaction to a perceived threat. Once it became clear that the march would go on, however, he supported it. While various labor unions supported the march, the AFL-CIO remained neutral.

Outright opposition came from two sides. White supremacist groups, including the Ku Klux Klan, were obviously not in favor of any event supporting racial equality. On the other hand, the march was also condemned by some civil rights activists who felt it presented an inaccurate, sanitized pageant of racial harmony; Malcolm X called it the "Farce on Washington," and members of the Nation of Islam who attended the march faced a temporary suspension.

Nobody was sure how many people would turn up for the demonstration in Washington, D.C. Some traveling from the South were harassed and threatened. But on August 28, 1963, an estimated quarter of a million people—about a quarter of whom were white—marched from the Washington Monument to the Lincoln Memorial, in what turned out to be both a protest and a communal celebration. The heavy police presence turned out to be unnecessary, as the march was noted for its civility and peacefulness. The march was extensively covered by the media, with live international television coverage.

The event included musical performances by Marian Anderson; Joan Baez; Bob Dylan; Mahalia Jackson; Peter, Paul, and Mary; and Josh White. Charlton Heston—representing a contingent of artists, including Harry Belafonte, Marlon Brando, Diahann Carroll, Ossie Davis, Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne, Paul Newman, and Sidney Poitier–read a speech by James Baldwin.

The two most noteworthy speeches came from John Lewis and Martin Luther King, Jr. Lewis represented the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, a younger, more radical group than King's. The original text to his speech had circulated throughout the day and the march leaders were able to convince him to tone down his rhetoric and remove the most inflammatory portions. What he did deliver was still the most explicitly radical speech of the day. He said, in part:

The revolution is at hand, and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery. The nonviolent revolution is saying, "We will not wait for the courts to act, for we have been waiting hundreds of years. We will not wait for the President, nor the Justice Department, nor Congress, but we will take matters into our own hands, and create a great source of power, outside of any national structure that could and would assure us victory." For those who have said, "Be patient and wait!" we must say, "Patience is a dirty and nasty word." We cannot be patient, we do not want to be free gradually, we want our freedom, and we want it now. We cannot depend on any political party, for the Democrats and the Republicans have betrayed the basic principles of the Declaration of Independence.

Dr. King's speech remains one of the most famous speeches in American history. He started with prepared remarks, saying he was there to "cash a check" for "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness," while warning fellow protesters not to "allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. But then he departed from his script, shifting into the "I have a dream" theme he'd used on prior occasions, drawing on both "the American dream" and religious themes, speaking of an America where his children "will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character." He followed this with an exhortation to "let freedom ring" across the nation, and concluded with:

And when this happens, when we allow freedom to ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last, free at last. Thank God Almighty, we are free at last."

When I talk about the impact of Bob Dylan upon American culture in the last half century I always include the image of the 23 year-old folksinger on the stage in the shadow of the Washington Monument performing as, in effect, the warm up act for Dr. King's "I have a dream" speech.