Lost in piles of budget exploitation records, Glen Campbell meets Bob Dylan and makes a gem of an album that’s not going to see a CD reissue anytime soon.

Back in the early ‘70s, I wasn’t in the mood for guys singing about rhinestone cowboys or Wichita linemen, especially with full orchestras and background singers. It was a time of very serious artists with serious acoustic guitars who played mostly unaccompanied and always wrote their own serious songs (how could you sing about feelings that weren’t your own?).

Dave was this banjo-playing bartender friend of mine who let me drink for free in a dark roadside motel bar just outside of the town I was living in at the time. I kept him company and watched him win hundreds of dollars from road-weary truck drivers with his “red card, black card E.S.P.” card trick that, countless beers and truckers later, I finally figured out how to do. Late one evening at his apartment somehow Glen Campbell’s name came up in a conversation and I sneered and made some comment about "rhinestone linemen." A little later he put on a record and said, “Listen to this.” It was some bluegrass track and in the middle was a totally monster mandolin solo.

“Holy smokes!” I said. “Who’s that mandolin player?”

“That isn’t a mandolin player.” My friend said. “That’s Glen Campbell on a 12-string.”

While I didn’t become a fan at the time, that was later after I realized that Jimmy Webb was a genius, I did stop sneering and developed a respect for Campbell, Tommy Tedesco, Howard Roberts, Hank Garland and another hundred faceless session musicians I’ve learned about over the years.

If you ever see The Monkees video for “Valerie,” notice how the camera cuts from a wide shot of the whole band to a super tight close up of the hand on the fret board of Mike Nesmith’s Gretsch White Falcon guitar during the solo. If I had a favorite Monkee it would be Mike, no doubt. His solo material is really quite good. But the guitar solo in “Valerie” is about as beyond his abilities as a guitarist as James Joyce’s “Ulysses” is beyond mine as a writer (or a reader for that matter). If you could see the arm attached to that hand it’d be attached to Glen Campbell [*actually, it turns out that's an internet legend; the guitarist is really session legend, Louis Shelton].

As the rules of irony might dictate, during the Glen Campbell scorning period of my life my musical idol was Bob Dylan. It was Dylan after all who turned the definition of folk “authenticity” on its head and in the wake of his work nobody was authentic if they weren’t singing their own songs (and another strike against the Rhinestone Cowpoke).

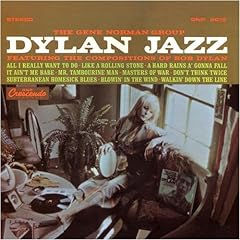

Where the irony enters is in the form of this album,

Dylan Jazz. An album of Dylan songs done instrumentally in small jazz-combo arrangements by the Gene Norman Group and lifted up into someplace special by the guitar playing of Glen Campbell.

The GNP Cresendo label was the creation of Gene Norman, whose jazz club, The Crescendo, was a famous Sunset Strip nightclub in the 1940s and ‘50s and home to performances by every major jazz artist of that era. Gene Norman started his GNP label in 1954 and later struck gold with releases of Star Trek and Trek-related albums. Gene Norman told me the funniest joke I ever heard.

I met him in his hotel room at a NARM convention in San Francisco about six or so years back. He was in his late-70s and sat on the edge of his bed smoking a huge cigar.

“I heard a good joke the other day.”

There was a theatrically long pause for effect.

“I met a man who didn’t own a record label.”

You can’t see me but I’m still laughing almost too hard to type.

Gene showed me his passport. Where it has occupation listed his had, “Impresario.” I still think it was among the coolest things I've ever seen.

Needless to say, Gene is relegated to playing the electric cash register in “The Gene Norman Group.” The musicians here are Jim Horn on sax and flute, Glen Campbell on guitar, Al Delory on piano, Lyle Ritz on bass, and the great Hal Blain on drums. The album was produced by Leon Russell and Snuff Garrett and sounds like everyone involved had a pretty good time in the process.

The sleeve here is a surprisingly hip quotation of the sleeve of Dylan’s 1965 LP “Bringing It All Back Home.” An issue of Time magazine lies on the table by a harmonica. The woman sits by an acoustic guitar and holds a tambourine. The covers of two older Dylan LPs are to the bottom right, the top of his 1962 debut record just peeking into the frame.I have a fatal weakness for guitar players, a fact well illustrated by the leaning tower of record crates across the room, and this is one wonderful jazz guitar album.

Most tracks are only briefly recognizable during an opening passage where the melody line can be heard, then take off into some terrific flights of fancy mostly via Campbell’s outrageous guitar playing. My friend, Scott Ballentine, is one of the better guitar players in Indianapolis, and his taste in guitar music is pretty brutal. I’ve never come up with a favorite airy arty solo finger-style acoustic guitar record that he didn’t ridicule within the first 10 or 11 seconds. Some of my all-time favorite guitar players, such as Larry Coryell and Lenny Breau, don’t rate much above a begrudgingly mumbled “Mmmm yeah, they’re OK.” It has become my mission to find guitar records that slap that “show me something” smile off his face, and I am happy to say that this one left both cheeks stinging.

Scott, like me but even more so, is not dazzled by shows of technical virtuosity alone. There’s got to be somebody there. There’s got to some feeling, some heart, some soul in the notes and in the spaces between the notes or it’s just not going to be worth going back to a second and third time.

Dylan Jazz is stuffed full of spirit, heart, soul, whatever you want to call it. A good deal of it flows from Glen Campbell’s fingers on the lesser-known “Walkin’ Down the Line,” in particular. Songs that are musically a bit on the monotonic side like “Masters of War” and “A Hard Rains A’ Gonna Fall,” are opened up melodically wider than I might have thought possible.

I’ve collected Dylan LPs for over 20 years and have never come across this until Punkin Holler Boy, John Sheets, gave me an old beat up copy he had lying around. I just slightly upgraded that one, courtesy of eBay, but still kick myself over a German pressing on the Vogue label I missed about a month or two back. The first time I saw Lou Reed’s

Metal Machine Music on CD I realized that just about anything might come out on disc eventually, but I’m not holding my breath waiting for this one. However, I was surprised as all get out to just now find that the album is available from iTunes as a download.

In the above photos Lohan prepares for her shoot. The first time I saw these images was a bit like seeing Christian Bale in the Bob Dylan anti-biopic I'm Not There, it took me a little while to figure out that the distance between the subject (Bale/Lohan) and the object (Dylan/Monroe) was intentional and calculated. In these photos Lohan eschews the airbrushing and make-up that might have removed that tattoo or eliminated the freckles and, having made a study of the original photos, her expressions seem to explode with intent as well.

In the above photos Lohan prepares for her shoot. The first time I saw these images was a bit like seeing Christian Bale in the Bob Dylan anti-biopic I'm Not There, it took me a little while to figure out that the distance between the subject (Bale/Lohan) and the object (Dylan/Monroe) was intentional and calculated. In these photos Lohan eschews the airbrushing and make-up that might have removed that tattoo or eliminated the freckles and, having made a study of the original photos, her expressions seem to explode with intent as well.